Hoof Pastern Axis

- Marc Jerram

- Dec 18, 2025

- 10 min read

Introduction

The hoof pastern axis HPA is a foundational concept in hoof anatomy farriery and equine biomechanics. It describes the alignment relationship between the dorsal surface of the hoof wall and the dorsal surface of the pastern encompassing the proximal phalanx P1 middle phalanx P2 and distal phalanx P3. When viewed laterally the ideal hoof pastern axis presents as a straight continuous line from the dorsal pastern to the toe of the hoof. This alignment is not merely an aesthetic ideal it reflects a balance of skeletal orientation soft tissue tension and load distribution through the limb. Deviations from a normal hoof pastern axis alter how forces are transmitted through bones joints tendons ligaments and the hoof capsule itself with significant implications for soundness performance and long term limb health (Clayton 2016).

The concept of the hoof pastern axis has evolved alongside advances in veterinary science and farriery. Historically farriers relied primarily on external landmarks and visual appraisal to assess alignment often guided by tradition and empirical experience. While these methods remain valuable modern research has demonstrated that external hoof appearance does not always accurately reflect internal skeletal alignment particularly in horses with chronic hoof capsule distortion previous pathology or long standing imbalance (Dyson 2011). As a result the hoof pastern axis must be understood as both an external visual guide and an internal anatomical relationship.

Understanding the hoof pastern axis requires appreciation of both static conformation and dynamic function. While a horse may appear to have a particular axis when standing square on a level surface the true mechanical consequences are revealed during locomotion when the limb is subjected to cyclical loading acceleration deceleration and uneven terrain. The interaction between limb conformation trimming shoeing surface and workload all influence how the axis functions over time. Farriery interventions that seek to influence the hoof pastern axis must therefore be grounded in anatomy physiology and a realistic understanding of tissue adaptation (Parks 2012).

The Normal Hoof Pastern Axis

A normal hoof pastern axis is traditionally defined as a straight line when the dorsal surface of the pastern and the dorsal hoof wall are viewed from the side. In this configuration the angles of P1 P2 and P3 are harmoniously aligned allowing compressive and tensile forces to be distributed evenly through the limb. The joints of the distal limb are positioned to function within their optimal ranges of motion reducing abnormal stress on articular cartilage subchondral bone and periarticular soft tissues (Stashak and Hill 2014).

In the normally aligned limb the coffin joint pastern joint and fetlock joint share load in a coordinated manner. During weight bearing the fetlock descends the pastern joints flex slightly and the hoof capsule deforms to dissipate concussion. The digital cushion and lateral cartilages expand while the hoof wall bars sole and frog act together as a functional unit. A normal hoof pastern axis supports this integrated mechanism ensuring that no single structure is overloaded at the expense of others (Bowker 2003).

From a biomechanical perspective a normal hoof pastern axis facilitates efficient energy transfer during locomotion. As the hoof lands ground reaction forces are absorbed and redirected up the limb along the skeletal column. During mid stance the limb supports the weight of the horse with minimal rotational torque at the joints. At breakover the alignment allows the deep digital flexor tendon and superficial digital flexor tendon to function within their physiological ranges while the navicular apparatus experiences controlled evenly distributed loading (Clayton et al. 2011).

In farriery, maintaining or restoring a normal hoof pastern axis is often a central objective. This involves managing toe length heel height and solar plane orientation so that the hoof capsule supports the natural alignment of the limb. Importantly a normal axis does not imply that all horses should share identical hoof angles. Individual conformation breed characteristics and limb proportions influence what is normal for a given horse. A Thoroughbred with long sloping pasterns may have a markedly different hoof angle from a native pony with short upright pasterns yet both may exhibit a straight hoof pastern axis relative to their own anatomy (Parks and O Grady 2013).

Radiographic assessment has become an invaluable tool in confirming a normal hoof pastern axis. Lateromedial radiographs allow evaluation of the alignment of P3 relative to the hoof capsule as well as the relationship between the phalanges and the ground. This is particularly important in cases where flares long toes crushed heels or capsule migration obscure true alignment. When the axis is normal the dorsal hoof wall is generally parallel to the dorsal surface of P3 and the pastern bones align smoothly above it without abrupt angular changes (Dyson and Murray 2007).

Learn more about Radiography from The Hoofcare Companion Podcast below:

Functional Significance of a Normal Axis

The functional significance of a normal hoof pastern axis extends beyond static alignment. It has direct implications for stride length limb flight arc and overall movement efficiency. Horses with a well maintained normal axis often demonstrate fluid economical gaits with consistent foot placement and symmetrical loading patterns. This efficiency reduces fatigue and supports sustained athletic performance across a wide range of disciplines (Clayton 2016).

Tendons and ligaments of the distal limb are particularly sensitive to changes in alignment. In a normal axis these structures operate close to their optimal elastic limits storing and releasing energy with minimal microtrauma. This is especially important for the superficial and deep digital flexor tendons which act as dynamic stabilisers during stance and propulsion. The suspensory apparatus similarly benefits from balanced loading reducing the risk of cumulative strain and fibre damage (Stashak and Hill 2014).

From a pathological standpoint a normal hoof pastern axis is associated with a lower incidence of many common distal limb disorders. While no alignment guarantees freedom from injury maintaining normal relationships reduces excessive focal stress on joints tendons and ligaments. Consequently achieving and preserving a normal axis is widely regarded as both a preventative and performance enhancing goal in farriery and hoof care (Parks 2012).

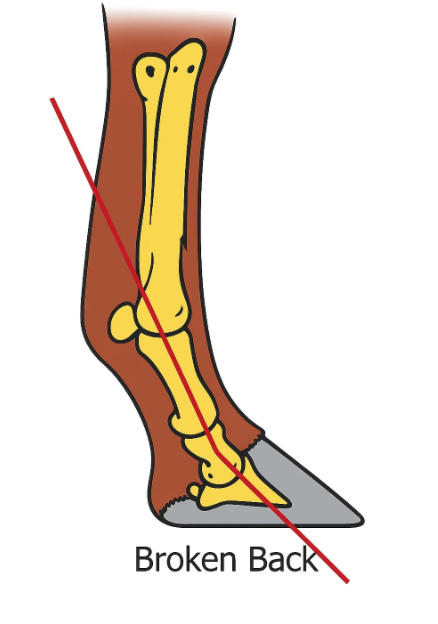

The Broken Back Hoof Pastern Axis

A broken back hoof pastern axis occurs when the dorsal hoof wall angle is lower than the angle of the pastern resulting in a backward deviation of the alignment line when viewed laterally. In practical terms the hoof appears laid back relative to the pastern. This configuration is commonly associated with long toes low or underrun heels and delayed breakover and is frequently encountered in both shod and unshod horses (O Grady and Poupard 2003).

Anatomically a broken back axis alters the orientation of the distal phalanx within the hoof capsule. The palmar angle of P3 may be reduced to zero or become negative shifting load toward the palmar structures of the foot. As the deep digital flexor tendon passes over the navicular bone tension within the tendon increases resulting in elevated compressive forces on the navicular apparatus. Over time this altered loading environment can contribute to structural and degenerative changes within the bone tendon and associated fibrocartilage (Dyson 2011).

The broken back axis is often compounded by hoof capsule distortion. As the toe migrates forward and the heels collapse the dorsal hoof wall no longer reflects the true orientation of P3. This disconnect between internal anatomy and external appearance can mislead visual assessment and lead to inappropriate trimming decisions if radiographic information is not considered. The longer the imbalance persists the more entrenched the distortion becomes making correction increasingly challenging (Parks and O Grady 2013).

Clinical and Performance Implications of a Broken Back Axis

The clinical implications of a broken back hoof pastern axis are extensive. Horses with this alignment frequently show signs of discomfort within the caudal foot including shortened stride length reluctance to land heel first toe first landings and increased sensitivity on hard or uneven surfaces. In performance horses subtle changes in gait may precede overt lameness sometimes for many months (Dyson and Murray 2007).

The increased strain placed on the deep digital flexor tendon and navicular region predisposes affected horses to conditions such as navicular syndrome deep digital flexor tendon lesions and navicular bursitis. The coffin joint may also be subjected to abnormal stresses particularly during breakover increasing the risk of degenerative joint disease. At the level of the fetlock the broken back axis can contribute to excessive hyperextension placing additional load on the suspensory ligament and distal sesamoidean ligaments (Stashak and Hill 2014).

From a farriery standpoint addressing a broken back axis requires careful incremental correction. Reducing excessive toe length improving heel support and facilitating earlier breakover are common objectives. However rapid or aggressive changes risk overloading structures that have adapted to the existing alignment. Successful management often involves a collaborative approach between farrier and veterinarian guided by radiographic monitoring and regular reassessment of comfort and gait (Parks 2012).

The Broken Forward Hoof Pastern Axis

A broken forward hoof pastern axis is characterised by a dorsal hoof wall angle that is steeper than the angle of the pastern producing a forward deviation when viewed laterally. In this configuration the hoof appears more upright in relation to the pastern. Broken forward axes are commonly observed in horses with upright feet high heels or club foot tendencies and may be influenced by genetics growth patterns or previous injury (Redden 2003).

Anatomically the broken forward axis increases the angle of the distal phalanx relative to the ground often resulting in an increased palmar angle. While this may reduce tensile strain on the deep digital flexor tendon it alters joint loading patterns. The dorsal aspect of the coffin joint experiences increased compressive forces and the pastern joints may function closer to the limits of extension during stance increasing focal stress on articular cartilage (Dyson 2011).

The hoof capsule in a broken forward axis often displays limited deformation under load. The digital cushion and lateral cartilages may be underutilised reducing the hoof capacity for shock absorption. As a result concussion forces are transmitted more directly up the limb which can have implications for joints and soft tissues proximal to the foot particularly in horses working on firm surfaces (Bowker 2003).

Clinical and Performance Implications of a Broken Forward Axis

Horses with a broken forward hoof pastern axis often demonstrate a distinctive movement pattern. The stride may appear short and choppy with rapid breakover and limited heel expansion. While such horses may perform adequately or even excel in certain disciplines the reduced shock absorption associated with this alignment can increase cumulative stress on joints bones and soft tissues (Clayton et al. 2011).

Clinically a broken forward axis is associated with conditions such as dorsal coffin joint arthritis high ringbone and increased wear cracking or stress lines in the dorsal hoof wall. Concentration of forces on the dorsal aspect of the foot may also contribute to sole bruising reduced comfort on firm ground and earlier onset of fatigue during work (Stashak and Hill 2014).

Farriery intervention in cases of broken forward alignment must be approached with caution. Excessive lowering of the heels in an attempt to create a straighter visual axis can increase strain on the deep digital flexor tendon and navicular structures particularly in horses with inherent upright conformation. Instead emphasis is placed on optimising load distribution maintaining heel support and promoting functional balance rather than forcing conformity to an idealised alignment (Redden 2003).

Balancing Conformation, Function and Intervention

One of the central challenges in managing the hoof pastern axis lies in distinguishing between conformational variation and pathological imbalance. Not all deviations from a straight axis are inherently harmful particularly if the horse remains sound comfortable and capable of performing its intended work. Farriers and veterinarians must therefore evaluate alignment within the broader context of the individual horse rather than relying solely on visual ideals (Parks and O Grady 2013).

Factors such as age breed discipline footing and workload all influence how the hoof pastern axis functions over time. A young horse in growth may exhibit transient deviations that resolve with appropriate management while an older horse may have long standing adaptations that should not be aggressively altered. Dynamic assessment including observation of the horse in motion provides critical insight into how alignment affects function during real world use (Clayton 2016).

Radiographic evaluation is an essential component of informed decision making. By visualising the relationship between the hoof capsule distal phalanx and pastern bones practitioners can differentiate between cosmetic imbalance and true skeletal misalignment. This information supports targeted evidence based farriery strategies that prioritise long term soundness and comfort (Dyson and Murray 2007).

Long Term Consequences of Hoof Pastern Axis Imbalance

Chronic imbalance of the hoof pastern axis whether broken back or broken forward can have cumulative effects on the musculoskeletal system. Abnormal loading patterns accelerate wear of articular cartilage increase stress on tendons and ligaments and compromise the shock absorbing capacity of the hoof. Over months or years these changes may manifest as degenerative joint disease chronic soft tissue injury or recurrent lameness limiting performance and longevity (Stashak and Hill 2014).

In younger horses inappropriate management of the hoof pastern axis can influence skeletal development joint orientation and soft tissue adaptation. Early informed intervention can help guide healthy limb development and reduce the risk of permanent conformational defects. Conversely poorly considered corrections may introduce new stresses with long term consequences for soundness and welfare (Redden 2003).

Conclusion

The hoof pastern axis represents a critical intersection between anatomy biomechanics and farriery practice. A normal axis supports efficient movement balanced force distribution and long term limb health while broken back and broken forward alignments introduce distinct biomechanical challenges and potential pathologies. Understanding these relationships allows farriers and veterinarians to make informed decisions that respect both form and function.

Effective management of the hoof pastern axis requires a holistic horse centred approach that integrates anatomical knowledge careful observation radiographic assessment and thoughtful intervention. Rather than pursuing a rigid visual ideal the goal should be to optimise function within the context of each horse unique conformation and use. When approached in this way the hoof pastern axis becomes not simply a line on the side of the hoof but a dynamic indicator of equine health performance and welfare.

References

Bowker, R.M. (2003) ‘Contrasting structural morphologies of the equine digital cushion in young and mature horses’, Equine Veterinary Journal, 35(6), pp. 612–618.

Clayton, H.M. (2016) The dynamic horse: A biomechanical guide to equine movement and performance. Mason, MI: Sport Horse Publications.

Clayton, H.M., Hobbs, S.J. and Richards, J. (2011) ‘The effect of hoof angle on the gait of the horse’, Equine Veterinary Journal, 43(4), pp. 395–401.

Dyson, S.J. (2011) Diagnosis and management of lameness in the horse. 2nd edn. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

Dyson, S.J. and Murray, R. (2007) ‘Magnetic resonance imaging of the equine foot’, Clinical Techniques in Equine Practice, 6(2), pp. 129–140.

O’Grady, S.E. and Poupard, D.A. (2003) ‘Proper physiologic horseshoeing’, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice, 19(2), pp. 333–351.

Parks, A.H. (2012) ‘Form and function of the equine digit’, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice, 28(3), pp. 355–372.

Parks, A.H. and O’Grady, S.E. (2013) ‘Chronic laminitis: Current concepts’, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice, 29(2), pp. 273–285.

Redden, R.F. (2003) ‘The equine club foot’, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice, 19(2), pp. 351–368.

Stashak, T.S. and Hill, C. (2014) Adams’ lameness in horses. 6th edn. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Comments